I want to direct you today to this story by Austin Meek at The Athletic about former University of Michigan football players who are haunted by the sexual abuse they experienced at the hands of team doctor Robert Anderson for the entirety of his 35-year career as team physician. The story is worth the price of a year’s subscription to The Athletic, so seriously, go subscribe and read it now. Meek took on a sensitive topic and dealt with it with deft and care.

However, despite how much I respected the story, one day later there is still something about it that is nagging at me. In answering the question of how such abuse could be allowed to continue for so long, the piece leans on former (now deceased) Athletic Director (AD) Don Canham and administrators in the upper reaches of the university as the clear villains. Like sexual abuse in other large institutions now being uncovered in American life, we’re told that these administrators were more interested in “protecting the school’s brand” than in protecting the students.

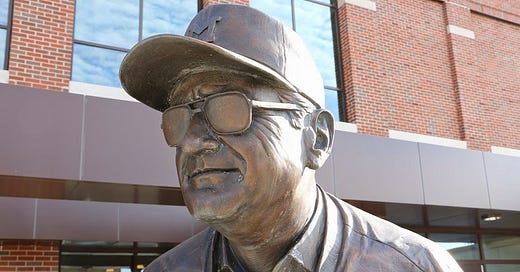

However, in the piece there is a tension as to how much Michigan football head coach Bo Schembechler should be thought of as one of these administrators. Was he just as much to blame as Canham? Did he equally work to “protect the ‘M’ brand” or was he largely not to blame? After reading the piece, I found the answers to these questions to be entirely straightforward. Schembechler is equally to blame in covering up Anderson’s abuse and Schembechler was just as interested in protecting the school’s brand as was Canham. Both men were part of the “army of enablers” who made Anderson’s abuse possible.

The evidence is clear. We’re told that Schembechler knew about the abuse as early as 1982 and that, while he told the reporting student in 1982 to tell Canham, Schembechler himself did nothing once no action was taken against Anderson. Additionally, Schembechler actually took over the AD position from Canham in 1988 and still kept Anderson on staff as the team doctor.

Despite this clarity on the questions of Schembechler’s culpability, the piece dances around the issue quite a bit. I don’t blame Meek for this as he was just following the lead of his interview subjects—most of whom are former Schembechler players still grappling with their feelings towards their former coach. We’re told that Schembechler “was a legend” who wouldn’t have had people around “if he didn’t trust and respect them.” We’re told that Schembechler maybe didn’t believe that men could possibly be sexually assaulted or that maybe the doctor’s actions could be interpreted through a medical lens. Multiple people in the article suggest that Schembechler was afraid of AD Canham and wouldn’t want to approach him about the issue. The student who reported the assault to Schembechler to this day says that “Bo was powerless” to do anything about the allegation himself—whether as a football coach or eventual AD.

Many other survivors of Anderson’s abuse push back against this narrative and clearly state that Schembechler should have offered continual support to the accusing student until action was taken by Canham or, at the very least, that he should have gotten rid of Anderson when he became AD in 1988.

I think the fact that this debate over Schembechler’s culpability in enabling Anderson’s abuse is still an open one for anyone is directly tied to a problem with how we tend to think about head college football coaches in American culture. Namely, head coaches (especially winning ones as Schembechler was) are often set up as idols—gods, if not God—so-called “father figures” who are responsible for the “kids” under their tutelage. We would be much better off if, instead, we saw them as bosses—mere men, human beings capable of good or evil or both. If we made the switch from “father” to “boss” in how we think about college football coaches, we would be able to think more clearly about whether or not the workplace that is college football was toxic and ripe for abuse.

This “father figure” fixation is at the root of why some people—even former abused players—can’t bring themselves to indict Schembechler. Compounding the sadness of this is the fact that many of these abused young men were fatherless as children, abused themselves as children, and/or watched their mothers suffer through abusive relationships growing up. So, as players, they turned to Schembechler to fill the void they felt in their own lives and now struggle with how their adoptive father could have left them open to the same kinds of abuse they experienced growing up.

What if Schembechler instead had been thought of as a boss and not a father? How might the situation have been different in the past or now? One can only speculate, but maybe there could be a more realistic evaluation of the man and his legacy because the question would simply be whether or not he created a good workplace environment. In thinking about Schembechler as a boss as opposed to a father, players would have been more likely to see that they were in a workplace and not a family—two very different institutions in American life. In a good workplace, you are encouraged to think of yourself as an adult worthy of respect as opposed to a “kid”—a child who needs to make sure you stay on dad’s good side. Such a workplace/boss framework as opposed to family/father may have empowered players to report what was happening to them.

Are things better now? Hardly—if anything they’re worse. College football is an even more gargantuan enterprise now than it was in Schembechler’s time which would further contribute to the inflated reputations of head coaches as something other than just a boss. For instance, Schembechler, in 1982, was the highest paid Big Ten coach and he made $150,000 a year—that’s about $400,000 in 2020 dollars. Today, as head coach at the same institution, Jim Harbaugh is the highest paid Big Ten coach at just over $8 million a year.

How might things start to change? How might players start to think about their situation through the workplace/boss framework as opposed to the family/father framework? Unsurprisingly, I think a functioning College Football Players Association (CFPA) would be a start. Such a new institution would encourage the players to think about their workplace as a workplace—one which needs functioning rules enforced by independent player representatives. So, if abuse is occurring in their possibly toxic workplace, the player would go to their player rep, not to their daddy/coach. The player rep would work through the CFPA to make sure the problem was addressed and not swept under the rug as the CFPA rep would be responsible to that institution and the players themselves as opposed to the university.

Such a new institution could empower players to think of themselves adult men as opposed to children—individuals who are capable of taking agency over their own lives and not deriving their worth from whether their daddy/coach liked them at any given moment. This, of course, doesn’t preclude a player liking their coach or having a good relationship with them. But, a CFPA would draw new boundaries around the relationship—correctly situating it as a workplace one and not a familial one. In doing so, at least in college football, we may be able to snuff out workplace abuse and toxicity before they have a chance to metastasize into one which festers for decades.